A small cohort of Royal Terns outfitted with lightweight GPS transmitters have returned to nest on the Cape Fear River, bringing with them data revealing new insights into their hemispheric migration and the conservation efforts that protect them along the way.

For researchers, the most interesting initial finding was that birds fanned out across the Americas, taking different migration routes to different wintering grounds. These places spanned from the Florida coastline to a hypersaline lake in the Dominican Republic to the wetlands of Panama Bay to a national park in Colombia.

The common thread between the birds, besides their North Carolina roots, was that each depended on natural areas and sanctuaries throughout the Americas that are supported by Audubon and our partners.

“This is the first time we have seen the routes that individuals take to get to their hemispheric wintering grounds,” said Dr. Kate Goodenough, Lead Ecologist at Larid Research and Conservation. “With this data we can begin to understand important conservation needs here in North Carolina and across the Americas.”

Uncovering the secret lives of Royal Terns

The tern project began in the spring of 2024 as a partnership with Dr. Goodenough, with the goal of better understanding the foraging movements of Royal Terns nesting on South Pelican Island in the Lower Cape Fear River. Thousands of Royal and Sandwich Terns nest on the island every year.

We deployed solar-powered GPS devices on 10 adult birds and set up a base station on the island that would receive data from the transmitters. Of those birds, six returned to the breeding colony this year.

One tern’s journey to Colombia

The GPS trackers allowed us to visualize for the first time their movements near their breeding grounds and the waterways, food resources, and roosting sites needed to help them thrive. Throughout the summer, they rely on big stretches of the North Carolina coast to forage for food, traveling to the far reaches of the upper Cape Fear River near Wilmington and as far south as Myrtle Beach in South Carolina.

Come mid-October, long after chicks had fledged and the season started to turn, many of our tagged terns began heading south for the winter.

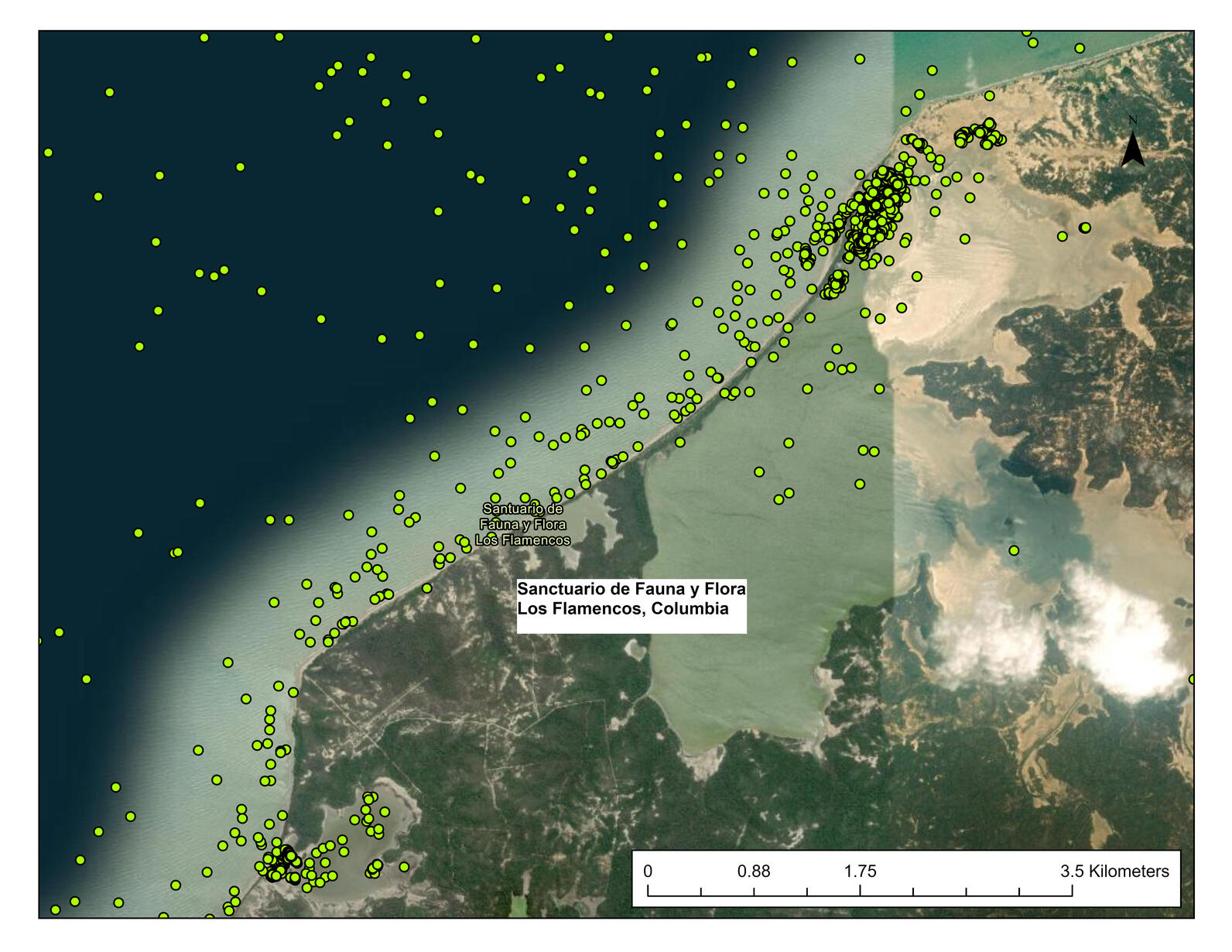

It took them four to five weeks to reach their winter destinations, mainly sticking to the coastline and making stops to rest and refuel. This map shows the migration route one of our tagged Royal Terns took to get to its wintering grounds in Colombia.

It left the breeding colony on South Pelican Island on July 28 but remained along the North and South Carolina coast for a few months. In mid-October it began moving south along the Atlantic Coast before reaching Big Talbot Island State Park in Florida. It stayed in Florida, inching farther south before arriving in Cuba on October 27. It continued through the Caribbean Sea to Jamaica where it stopped to forage for food before making its final jump to Colombia.

The tern first arrived at Isla de Salamanca on October 31 and then moved east along the coast to Los Flamencos Sanctuary, where it wintered along a stretch of coastline about 169km in length.

Los Flamencos Sanctuary is a 17,000+ acre reserve of marshes, lagoons, and dry forest on the northern shores of Colombia. It’s an Important Bird Area and designated wildlife sanctuary where hundreds of American Flamingos and other birds can be found.

In 2018, Audubon worked closely with the Colombian government and other partners to incorporate conservation of migratory, endemic, and endangered birds into the management of Los Flamencos, along with five other sanctuaries totaling 3.6 million acres. Audubon continues to work with park representatives in Colombia to coordinate monitoring and capacity-building whenever possible.

“Colombia is an incredibly biodiverse country with 1,900 species of birds,” Dr. Goodenough said. “Making this connection with one of our North Carolina terns solidifies how important Audubon’s hemispheric approach to bird conservation truly is.”

A hemispheric approach to bird conservation

Another tern traveled to Panama and spent the winter in the Panama Bay Wetlands of Importance Area.

Audubon worked closely with the Panama Audubon Society to develop a conservation plan for this and other important bird areas in the region. Partners also recently conducted an acoustic monitoring project to understand what birds use Panama Bay and what that can tell us about the health of the habitats in which they reside.

Seeing one of our terns spend the winter in the bay is evidence that these partnerships are benefiting birds on a hemispheric scale.

This project will not only help us conserve the sites and resources birds need during the breeding season but moves us towards Audubon’s hemispheric approach to bird conservation by giving us a better understanding of what areas birds need on both sides of their migration journeys.

“Discovering where our terns spend the winter is just one piece of the puzzle and helps us, and our colleagues in Latin America, broaden our focus to protecting birds and the places they need over their entire life cycles,” said Coastal Biologist Lindsay Addison.

On the horizon

So far, the GPS transmitters have uncovered important information about the areas Royal Terns need during their annual life cycles. The pilot project was so successful that this year, the team deployed more transmitters on Royal Terns and added Sandwich Terns to the project.

“We’re still looking through the data, but we already have a better understanding of their migrations as well as how and when they forage for food,” said Addison. “This is data we’ve never had access to before and will help us tremendously as we manage their populations into the future. It illustrates perfectly that the footprint of the resources they need to nest successfully and survive the non-breeding season extends far beyond the shores of their nesting islands.”

*All banding, marking, and sampling is being conducted under a federally authorized Bird Banding Permit issued by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Bird Banding Lab.