***Original post June 18***

With its elegant crest and bright orange bill, the Royal Tern lives up to its name. Every spring, this graceful waterbird returns from places as far south as Ecuador and Argentina to nest along the North Carolina coast, with one of the state’s largest colonies typically residing on South Pelican Island on the Lower Cape Fear River.

We have a lot of basic monitoring data about this colony from years of banding efforts (how many birds nest there, about how many chicks the colony produces annually), but little is known about their specific foraging and migration routes and the timing of these movements throughout their annual lifecycle. Having a better understanding of their day-to-day life could help us better protect the resources they rely on the most for breeding and raising chicks in North Carolina.

That’s why we’ve partnered with Dr. Kate Goodenough, Lead Ecologist at Larid Research and Conservation, to track nesting Royal Terns on the Cape Fear River. We want to better understand where they go to find food, how they get there, how long they leave their nests, and much more.

“Royal terns are one of our most heavily managed birds on the North Carolina coast, primarily due to their reliance on dredged-material islands and open sandy areas for nesting,” Coastal Biologist Lindsay Addison said. “We want them to continue to do well, which is why we are hoping to get a full picture of where and when they’re going for food during one of the most critical times of the year, the breeding season.”

This is the first such project with this species on the Atlantic Flyway and will allow us to track the full annual life cycle of terns, including their winter migrations and return to the North Carolina coast for the breeding season.

Last year we started putting field-readable bands on Royal Terns, which help reveal some migratory data. Field-readable bands have a unique number-letter combination that can be read in the field using a spotting scope or binoculars while the bird is wild and free. This project will go one step further, as it uses GPS technology to track the exact route these elegant waterbirds take and the full footprint of their movements during breeding and migration, rather than just showing a few stops along their journey.

While we’ve only just started using field-readable bands on Royal Terns, metal U.S. Geological Survey bands have been used since the 1970s on our terns in North Carolina. Thanks to Dr. John Weske and his long-term banding efforts, we know the exact age of a large population of birds on the Cape Fear River, since most Royal Terns were banded as chicks as part of his work.

“Having a good population of known-age birds is really rare,” Audubon Coastal Biologist Lindsay Addison said. “This will allow us to look deeper at the data we collect during this project and see if there are different foraging and migration strategies between age groups.”

Royal Terns on the Cape Fear River can live well into their 20s and 30s. We’ll be able to find out if older individuals, who know the river better and who have established where good foraging spots are, will have more efficient movements compared to their younger more inexperienced counterparts, and any other differences there might be.

Thanks to a grant we received in partnership with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, we’ll also be collecting poop samples from some of the chicks as they are being banded. Through a relatively new process called DNA barcoding, the fecal samples will reveal what taxa—sometimes down to the species level—the young birds are being fed.

The method will also identify the relative abundance of each taxa in their diet, suggesting which may be more important to them. Because small schooling fish are an important part of their diet, this information can be useful in fisheries management planning as well as in understanding how changes in presence and abundance of marine life due to climate change or other factors might affect the terns.

In order to get the GPS data loggers on the terns, our coastal team visited South Pelican Island, where thousands of Royal and Sandwich Terns breed in large groups every year. The colony nests on open bare sand, laying one egg per pair. With thousands of birds sitting on eggs, screeching in a chorus of communication, and gulls looking for their opportunity to snack on untended eggs, it is a difficult job to capture a few birds for tagging without causing too much disruption.

It takes Lindsay and her team less than ten minutes to anchor the boat, approach the colony, carefully trap five birds, and transport them back to the boat. Their fast work ensures the terns and other nesting birds are disturbed as little as possible.

Each bird collected has a metal U.S. Geological Survey band with a unique letter combination, allowing us to identify that individual and its age. Lindsay and Kate take a few measurements, harness the bird with a GPS data logger, and then release the bird back to its colony.

The tags will stay on the birds for about a year and a half before the harnesses will wear out and fall off. A solar-powered receiver installed on South Pelican Island, and paid for by Cape Fear Audubon, will receive data every hour and automatically upload that data to the cloud every eight hours.

This project is already revealing new insights. “So far, we can see that they like to forage at night, during incubation they travel about 20-30 kilometers offshore for food, and they like to forage upriver,” said Goodenough.

While they’re still sitting on eggs, they can stay off-colony longer as they don’t have young chicks to forage for and tend to. Once those eggs have hatched, they might stay closer to the colony so they can bring food back to their chicks and better protect them from the elements and predators.

“It will be interesting to see what parts of the river and coast they rely on the most for different phases of breeding and rearing young, as well as where they forage during migration,” said Goodenough.

After this pilot year, the team plans to put out additional loggers over the next couple of years in order to develop a robust picture of the terns’ movements. The results of this project will allow us to get a fuller picture of the resources used by Royal Terns and the timing of their breeding and migratory movements, adding to the information we can use to better manage and maintain their populations along the Atlantic Flyway.

*All banding, marking, and sampling is being conducted under a federally authorized Bird Banding Permit issued by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Bird Banding Lab.

***Update July 17***

Uncovering the secret lives of Royal Terns

Since putting out the tags at the end of May, we’ve been able to gather an entire month's worth of data, giving us a glimpse at the day-to-day lives of nesting Royal Terns.

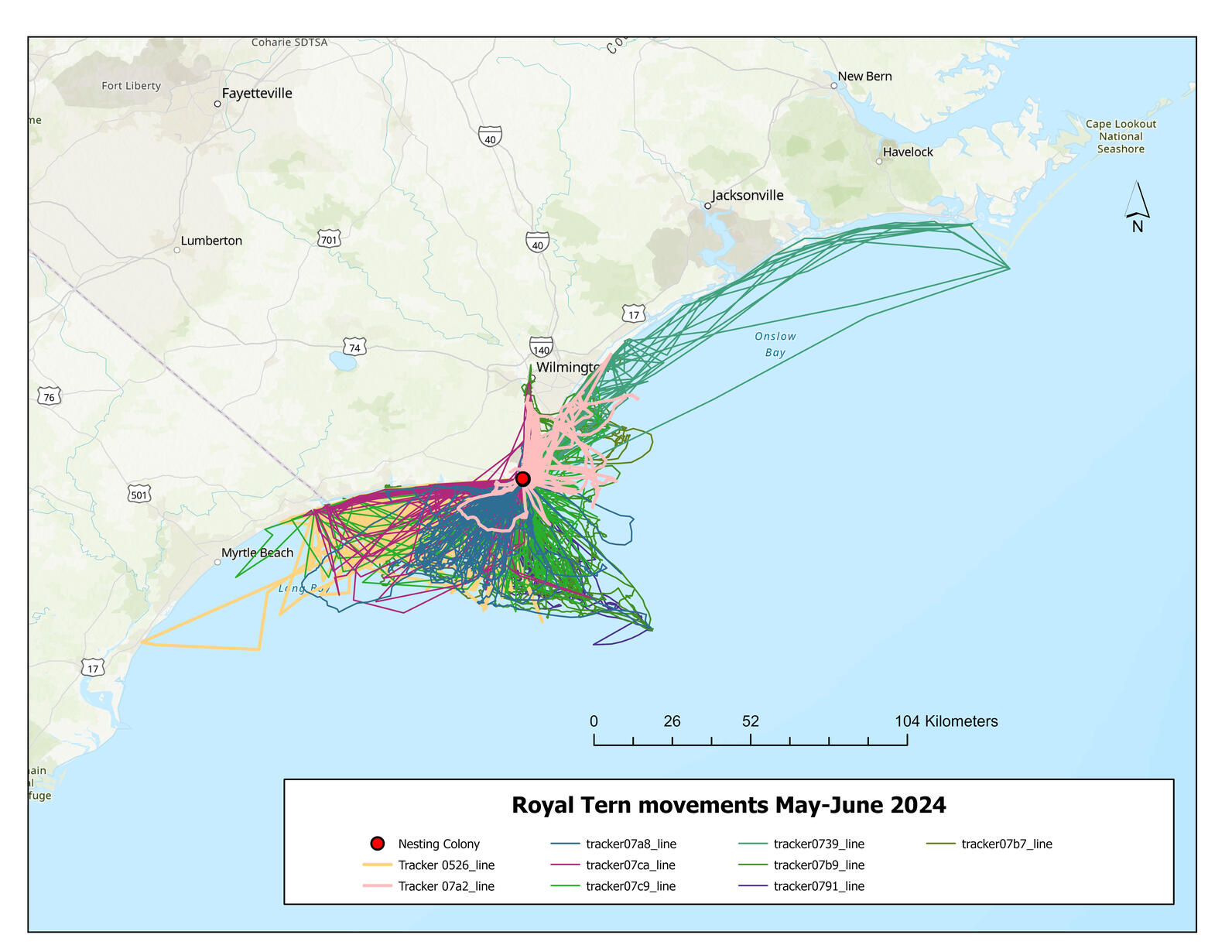

From the data we’ve gathered so far, you can see just how much of the coast these birds rely on during the breeding season. Their home base for the summer is South Pelican Island—where the birds' nest and raise chicks—but they also travel to the far reaches of the Upper Cape Fear River, the south end of Cape Lookout National Seashore, and down to Myrtle Beach in South Carolina to forage for food.

This data is a powerful example of just how vast the footprints of our coastal birds are and the importance of not only conserving their nesting grounds, but also the waterways, food resources, and roosting sites needed to help them thrive.

See where some of these Royal Terns traveled this June...

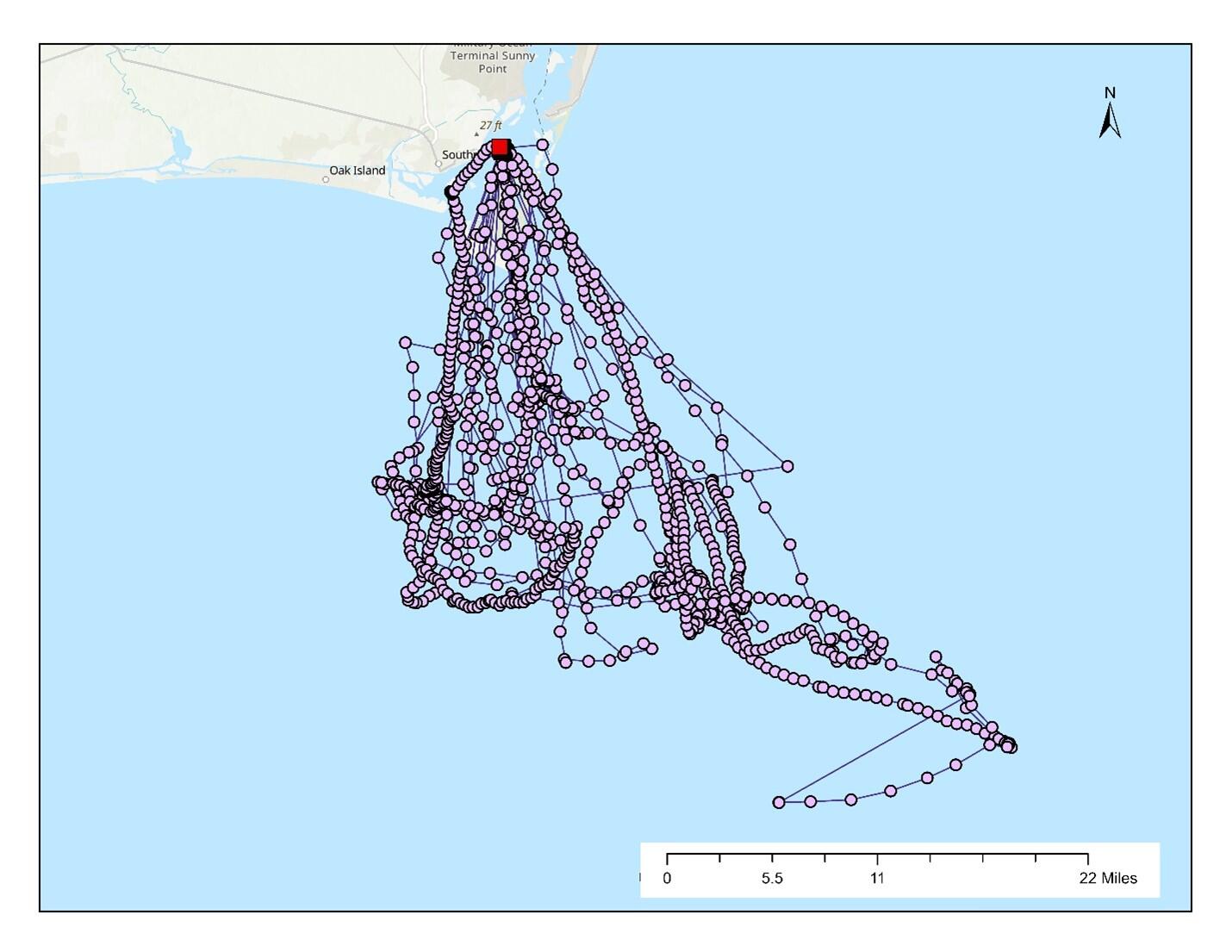

The nesting colony on South Pelican Island in the Lower Cape Fear River is shown by a red dot on the map. The pink dots show the movement of a single bird, who seems to like foraging out into the Atlantic Ocean, past Bald Head Island and Frying Pan Shoals.

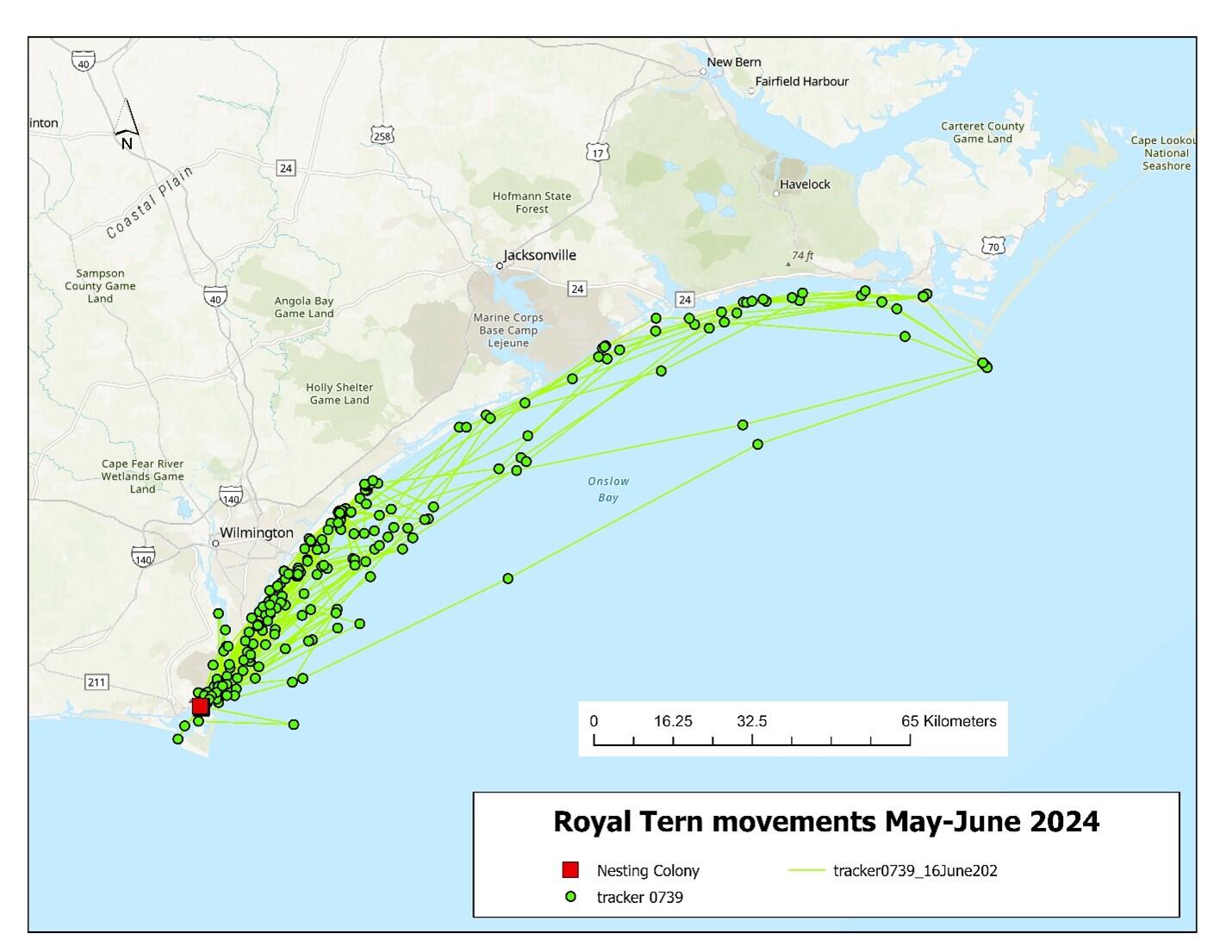

This bird takes a completely different path than the previous one, and likes to travel north along the North Carolina coast towards Cape Lookout National Seashore to forage, sometimes traveling up the Cape Fear River but mainly sticking to the Onslow Bight. The distance between the nesting colony and the point at South Core Banks of Cape Lookout National Seashore is about 95 miles one-way.

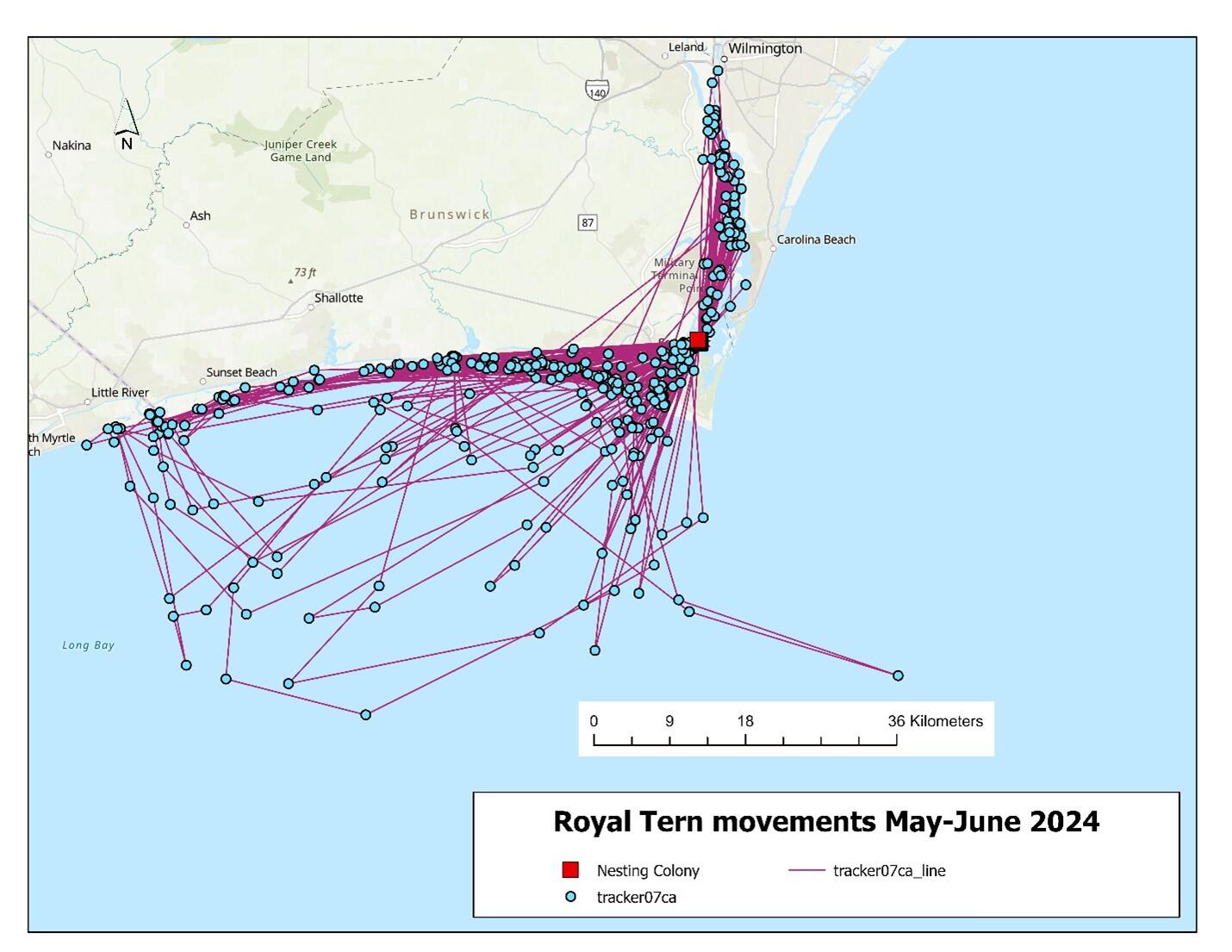

This bird (07ca) shows yet another foraging preference, sticking closer to the nesting colony and the upper reaches of the Cape Fear River, sometimes traveling upriver to downtown Wilmington and offshore of Brunswick County, and south to Myrtle Beach in South Carolina.

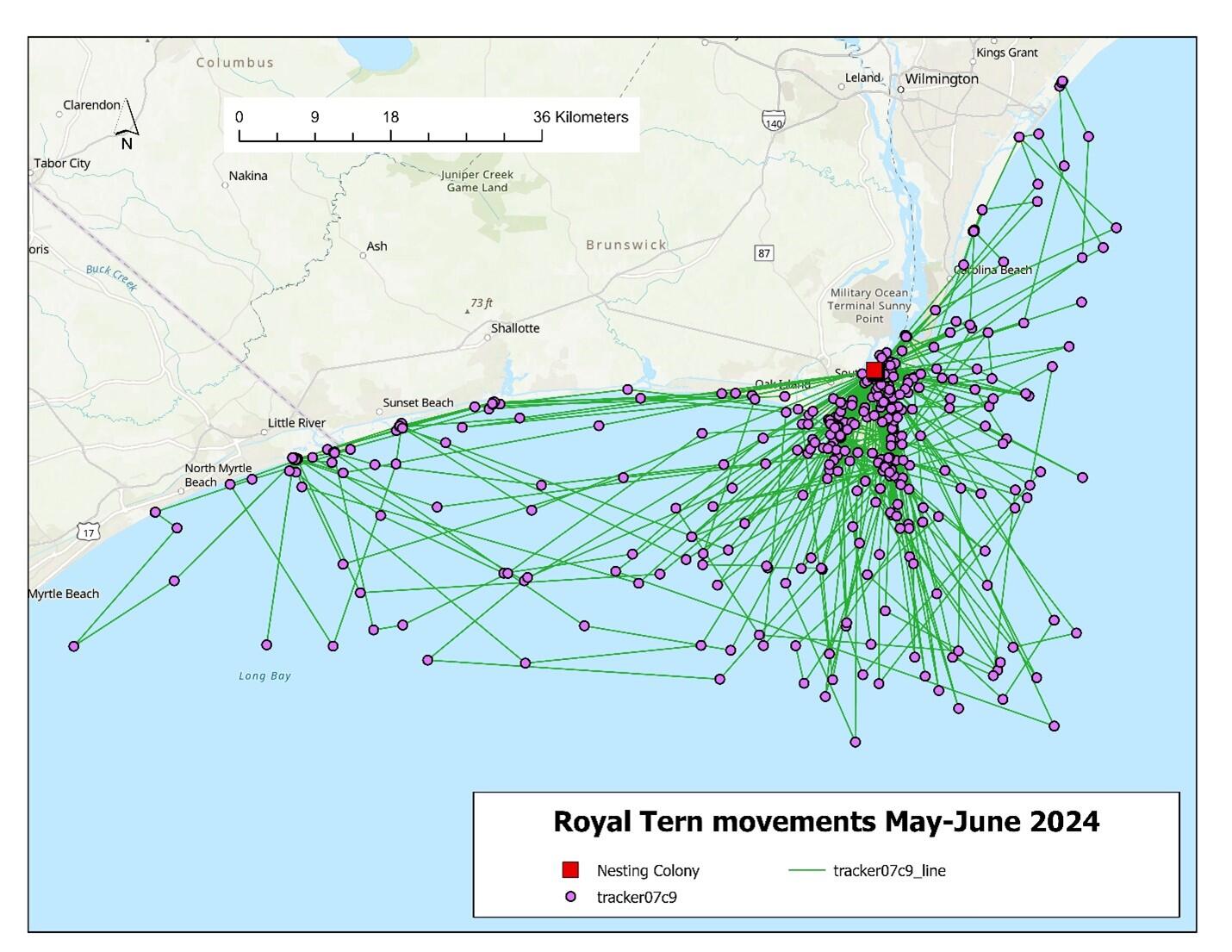

This bird (07c9) forages on the open ocean and hasn’t chosen to travel upriver. Instead, it likes the area surrounding Bald Head Island, sometimes going as far south as Myrtle Beach or as far north as Wrightsville Beach.

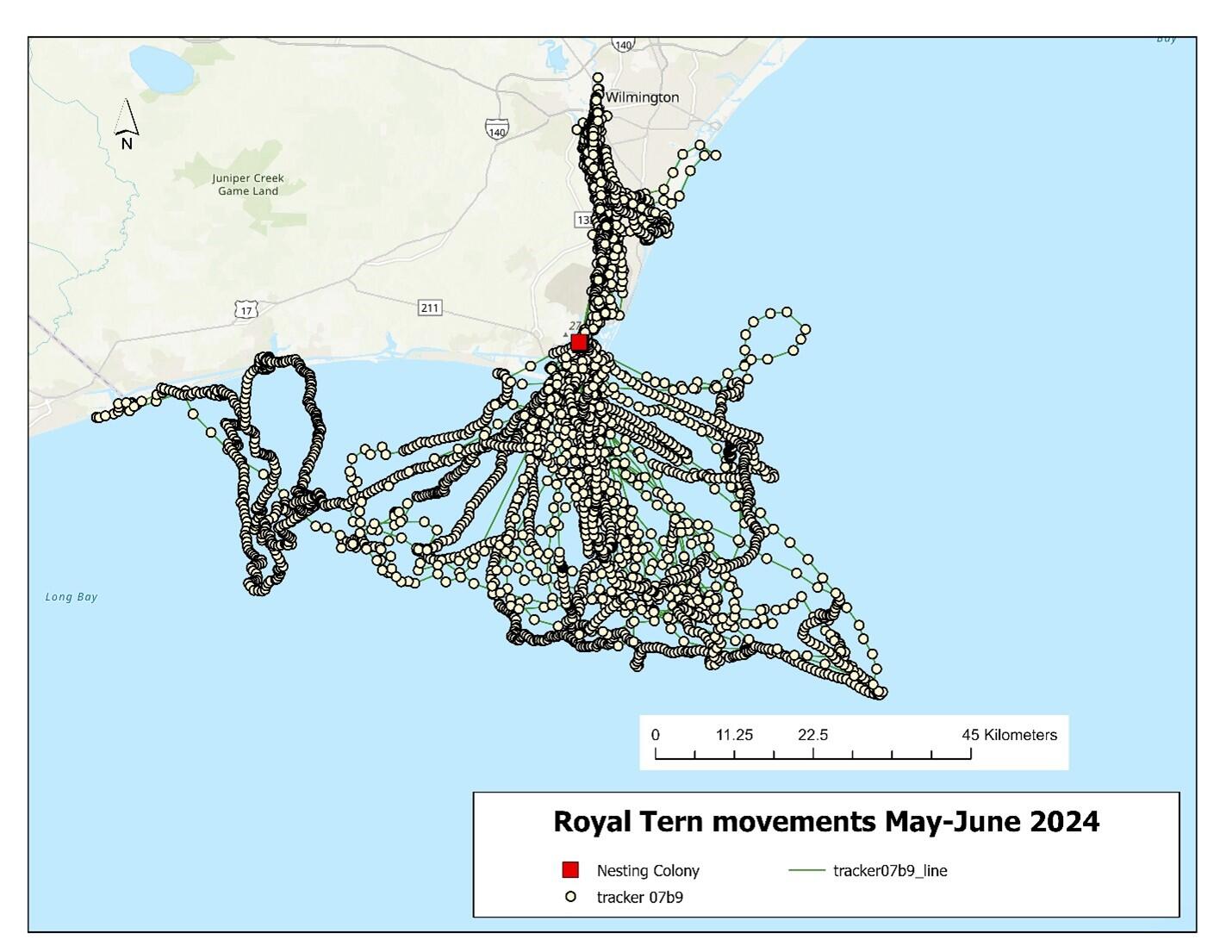

This bird (07b9) loves to move! Not only does it travel upriver for food, going as far north as Wilmington, but frequently goes more than 60 kilometers offshore into the Atlantic Ocean and south to the NC-SC border. Movements for this bird look a little different because we were testing the capability of tracking foraging routes at five-minute intervals rather than hourly.

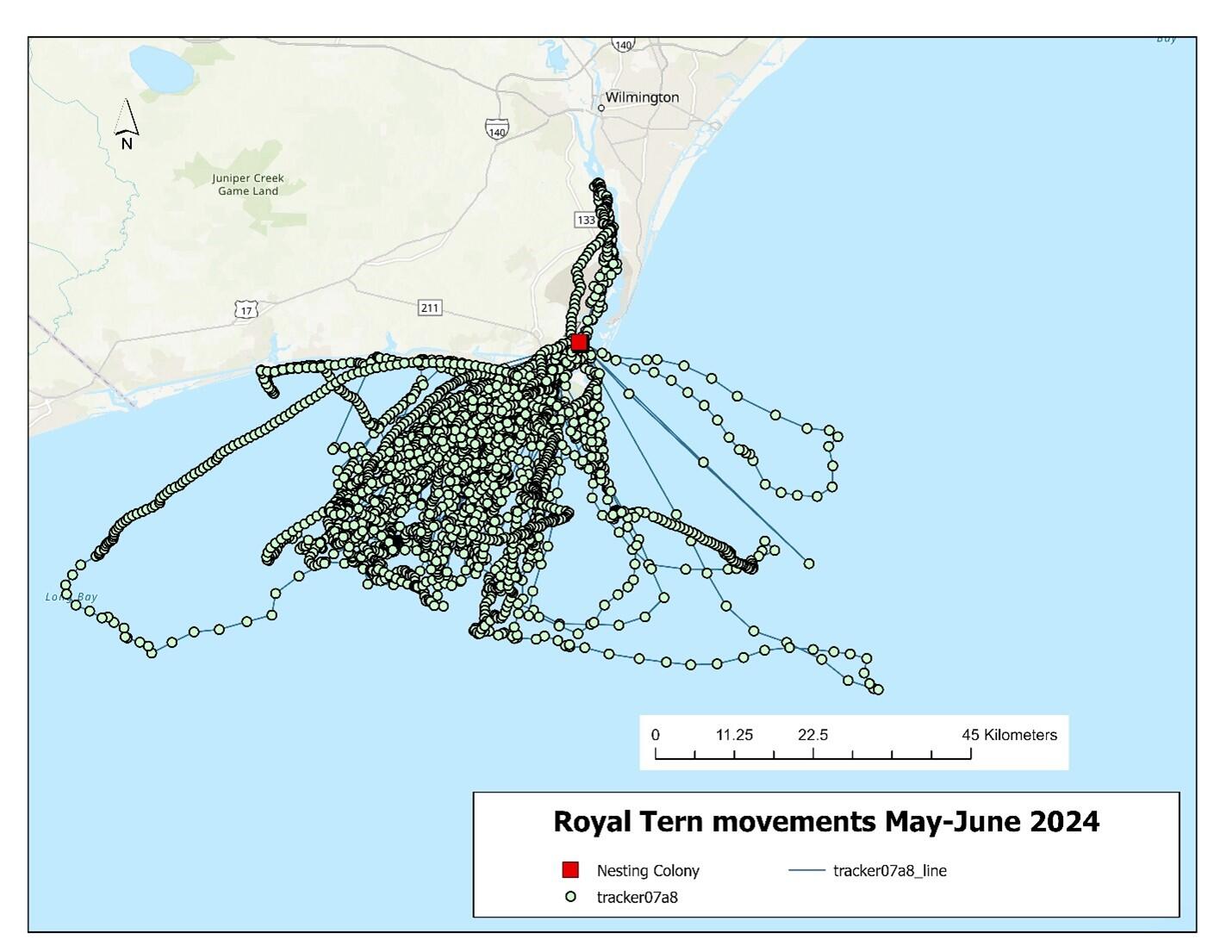

Another frequent flyer, this bird (07a8) similarly travels upriver but mainly forages offshore just southwest of Bald Head Island.

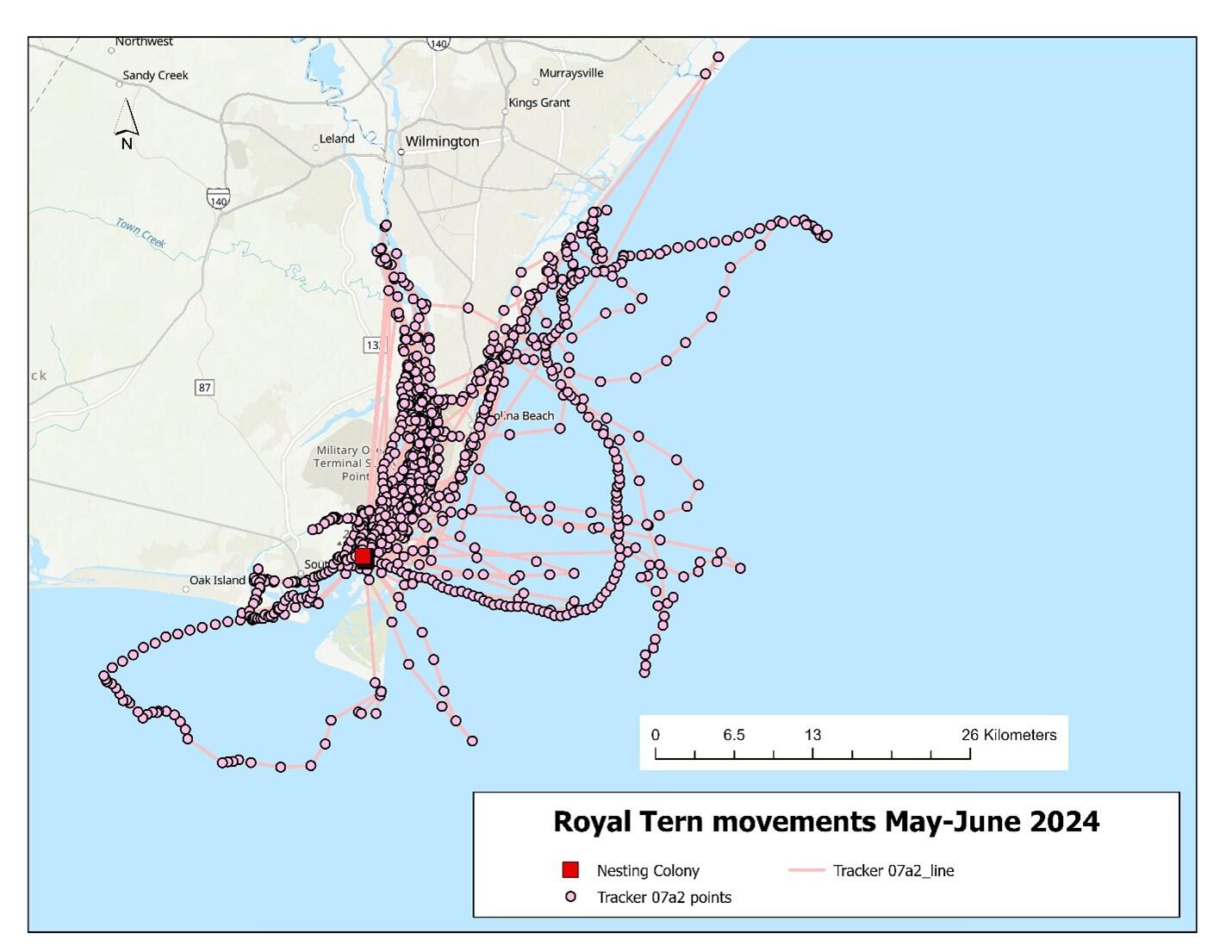

This bird (07a2) sticks to the rivers and lakes that it’s used to, mainly traveling upriver to forage, while sometimes scouring the waters off Carolina Beach for something to eat.

This last map shows the movements of all of our tracked birds from when they were tagged in May through the end of June. Here, we can start to piece together how unique each bird’s movements are as well as the places they rely on the most. The Upper Cape Fear River and the ocean waters south of Bald Head Island seem to be important places for these birds to forage. This is extremely valuable information that can help inform the management actions we take to make sure Royal Terns continue to thrive in our state.