As winter settles on the Cape Fear Region, it’s time to look back at how our coastal birds fared during the nesting season. Throughout the summer and early fall, volunteers spent more than 4,000 hours (that’s 167 days!) patrolling Audubon’s bird sanctuaries to protect nesting species.

Researchers and partner organizations visited as well, helping us survey species like American Oystercatcher and Wilson’s Plover. These are important actions we take every year to monitor and protect 40 percent of the state’s coastal nesting birds. But looking back, one of the biggest differences this year was a storm that took place in 2018.

Everyone will remember Hurricane Florence, which came (and stayed…and stayed) in the Cape Fear Region in September 2018. The 2019 nesting season was influenced in many ways by Florence’s landfall, some positive and some less so.

For beach-nesting birds on barrier islands, Florence brought boom times this past year. The powerful storm surge slammed into dunes on undeveloped islands, pushing them down and scattering their sand across the landscape to create open, sandy overwash fans, which are habitat prized by Least Terns, American Oystercatchers, and others.

As a direct positive result, this year set several records. The first and perhaps the biggest was the amazing Least Tern colony that settled on the north end of Lea-Hutaff Island. The tip of the island was in great shape for beach-nesting birds: open, sparsely vegetated expanses of sand stretched off into the distance, and when the birds arrived in the spring, numbers looked high.

We didn’t realize how high until our annual nest count. Staff and experienced volunteers walked sections of the beach, known as transects, calling out totals at the end of each one. After we summed them up—multiple times to make sure we were adding correctly—we were at 1,034 nests, the largest colony ever recorded in North Carolina in over 40 years of monitoring.

Even better, the colony suffered little disturbance from human visitors who respected the posted area and predation was low, so many hundreds of chicks survived to fledge. Similarly on one of our partner sites, Masonboro Island, a Least Tern colony of around 100 pairs formed on a new overwash fan. Though off-leash dogs were a challenge, it too fledged chicks. The island hasn’t had a colony that large in many years.

Oystercatchers and Plovers

American Oystercatchers and Wilson’s Plovers also benefitted from the overwash. On Lea-Hutaff, 12 chicks fledged from 24 nesting American Oystercatcher pairs, meeting the 0.5 fledglings-per-pair goal needed to grow their population. Both Lea-Hutaff and Masonboro Island logged record numbers of Wilson’s Plover pairs, at 49 and 52, respectively.

However, the story was different for oystercatchers on the Cape Fear River. Following Hurricane Florence in September 2018, there was no dissolved oxygen in the river for a month. This is important because even though oysters, fish, and other marine organisms live in the water, they need oxygen survive.

As a result, nearly all of the oysters on the Lower Cape Fear River died, leaving the American Oystercatchers without one of their primary food sources. The following spring, when it came time to nest, we found adult oystercatchers were underweight.

They delayed nest initiation, and some pairs didn’t lay eggs at all. As a result, productivity was down on the Cape Fear River, with only about 15 chicks fledged from 96 pairs. However, next year promises to be better: New oysters are starting to grow back on the old beds, a testament to the resilience of natural systems.

Fortunately, things were better for other species on the river. We were very pleased to see White Ibis return in large numbers to Battery Island this year. They gave the guests on the Cape Fear Garden Club’s Bird Islands Cruise a great show and successfully fledged many chicks. The Bald Eagles that had depredated the colony in 2017 fortunately stayed away.

Sea Turtles

While we focus our field work on nesting birds, we also manage and monitor nesting sea turtles on Lea-Hutaff Island, where 2019 was a banner year. We recorded 22 loggerhead sea turtle nests on the island, a record high for our site, and despite losing three entire nests to king tides and Hurricane Dorian, 1,620 hatchlings made it to the ocean. That’s our second highest total of hatchlings, just behind 2018.

American Oystercatcher Projects

We continued to coordinate the statewide American Oystercatcher banding effort. With partners from agencies around the state including the Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, and NC Wildlife Resources Commission, we banded 38 nesting adults and 129 chicks.

It was also the year of the statewide American Oystercatcher and Wilson’s Plover census. This project takes place every three years in order to detect trends in populations of nesting pairs and their distribution. With partners around the state, we helped to coordinate and carry out counts at 132 sites representing almost all of the state’s likely nesting habitat.

Preliminary results found 393 pairs of oystercatchers and 326 pairs of Wilson’s Plovers. The oystercatcher count was down about 40 pairs from 2017, and that could have been a result of Florence or king tides displacing pairs and making them harder to detect, while the Wilson’s Plover number was up.

Also this year we collaborated with Kate Goodenough, a PhD candidate from the University of Oklahoma, to pilot the use of dataloggers to monitor the fine-scale movement of nesting oystercatchers.

We trapped two adults, one at Rich Inlet and one on Masonboro Island. The tiny units they wore recorded their locations every 15 minutes within at least 20 meters of accuracy. We’ll be deploying more loggers next year, and the data will be used to model oystercatcher habitat use and assist in forecasting their patterns of distribution in North Carolina as the climate changes. Such modeling has the potential to aid in conservation planning, habitat enhancement or restoration, prioritization of site management actions, and land acquisition.

Black Skimmer Banding

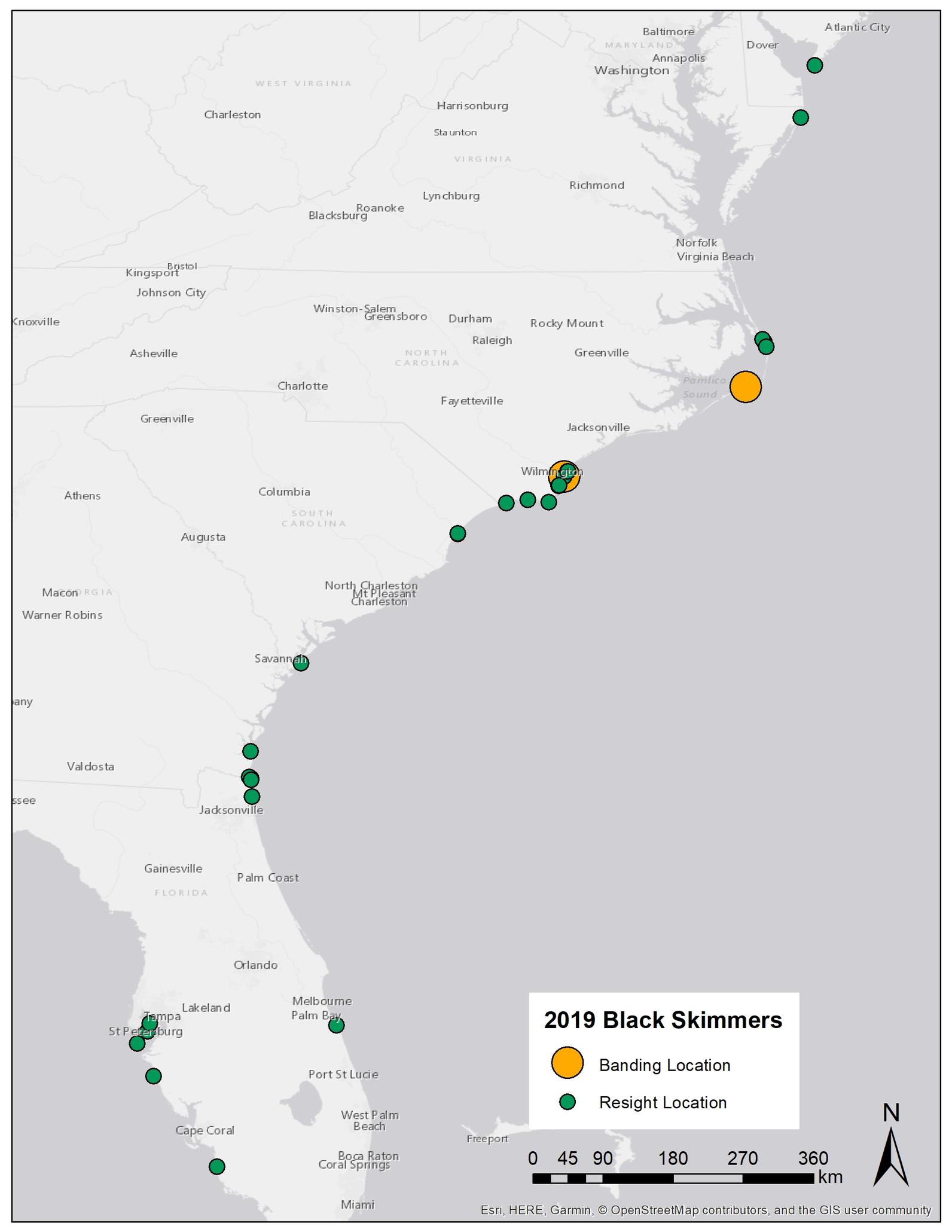

We started our Black Skimmer banding program with a bang—literally. The first banding event was hastened off the south end of Wrightsville Beach by a thunderstorm, but despite the rough start, we banded a total of 101 chicks in July and August. They have since fledged and migrated, and are being found again by observers around the southeast, as far south as Naples, Fla.

Volunteers Come Through

We’re lucky every year to have wonderful volunteers who act as bird stewards and help us with many other tasks, but 2019 was especially good. In all, we had 165 individuals volunteer their time and a total of 4,105 hours donated. By far the most exemplary volunteer experience came when Hurricane Dorian threatened North Carolina’s coast in late August.

Our postings on Wrightsville Beach and Lea-Hutaff Island were still up to protect the late fledges and roosting migrants that were lingering in them. We didn’t want to risk losing nearly 400 signs and posts in a storm surge, so at short notice, about 20 volunteers materialized to help take them all down before the storm arrived.

UNC-W Partnership Going Strong

It’s been a real pleasure to work with Dr. Ray Danner and his graduate and undergraduate students at UNC-Wilmington. This year we celebrated the graduation of two students, Rebekkah LaBlue and Lauren Schaale, who both studied difference facets of Least Tern nesting on Hutaff Island.

We also welcomed new collaborators from Dr. Danner’s lab, Juan Zuluaga, Marae Lindquist, and Evan Buckland who have been studying the winter and breeding ecology of Seaside Sparrows and Saltmarsh Sparrows at several Cape Fear area sites, including Lea Island. For their Lea Island work, they attached tiny transmitters to 14 sparrows to learn about the movements of nesting individuals.

Meanwhile, we entered our first nesting season of data collection for two graduate students, Anna Zarn and Angie Hall, who are working with Dr. Steve Emslie and Dr. Steve Skrabal in the UNC-W Department of Biology & Marine Biology and Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, respectively. With our staff, they collected sediment samples, shellfish, and oystercatcher eggshells and feathers in order to look for heavy metal contaminants in the Cape Fear River food web—important work because both birds and humans rely on the Cape Fear River.

Looking Ahead into 2020

Now we’re wrapping up the year with data entry and reporting and continuing our year-round shorebird monitoring and oystercatcher band resighting. In 2020 we’re anticipating building four new oyster reefs, the statewide Colonial Waterbird Census, more research projects, and more good times with volunteers.