In what is becoming a trend for many bird species, a recent survey revealed population declines for many beach-nesting birds, as well as other birds that rely on the undeveloped areas of our coast, from marshes to dredge islands.

It’s common for population numbers to fluctuate from year to year, but last year’s numbers are noteworthy because they are representative of a larger decline for many species. This is especially true for Black Skimmers, which saw a 47 percent decline in nesting pairs, compared to the 15-year average for the species.

“For many species, these aren’t the results we’d like to see,” Audubon Coastal Biologist Lindsay Addison said. “But the information can help site managers put what they’re seeing year to year in the context of these species’ overall populations in the state, which can help direct management actions, research, and partnerships.”

Nearly 50,000 nests and 21 species were counted in 2023 as part of the 15th colonial waterbird census in North Carolina. The effort takes place every three years and is coordinated by the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, with the help of several agencies and partners, including Audubon North Carolina. The results are reported to the North Carolina Waterbird Management Committee (NCWMC), which is made up of most agencies and other organizations that manage waterbirds in the state.

Since 1977, the census has allowed us to understand key trends among coastal waterbirds in the state and southeastern U.S. With this data, we can better determine their conservation status, population trends, and whether environmental changes and on-the-ground management actions are affecting their numbers.

The latest census continued to reveal the importance of dredged-material islands for nesting birds, especially in light of increased development along our coast. Finding barrier islands with enough room for birds to nest is increasingly rare, which has made management of undeveloped areas—and dredged-material islands—an important focus for Audubon.

This is why we work with the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers and the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission to direct the placement of dredged material on nesting islands—basically, rebuilding eroded islands using sand from dredging projects along the Cape Fear River and elsewhere—and to ensure that projects along the coast minimize impacts to waterbirds.

Even alongside these efforts, disturbance from dogs and people in or near posted nesting areas—especially on islands like Lea-Hutaff Island that are popular recreational destinations—have continued to threaten bird colonies. Traffic from commercial shipping vessels in the Lower Cape Fear River also contributes to nest failure, with wakes from large ships causing significant overwash on islands, sometimes washing away nests while also increasing erosion.

We’ve worked to address these threats by advocating for a lengthened bird sanctury closure window, monitoring busy nesting sites, and advocating for birds as the Port of Wilmington Expansion is being evaluated, along with our ongoing management work.

By the numbers

The Black Skimmer has had a rough go of it on our coast for the past several years. Plagued by flooding and predation, these notoriously late nesters are a high priority for Audubon and National Park Service partners at Cape Lookout National Seashore.

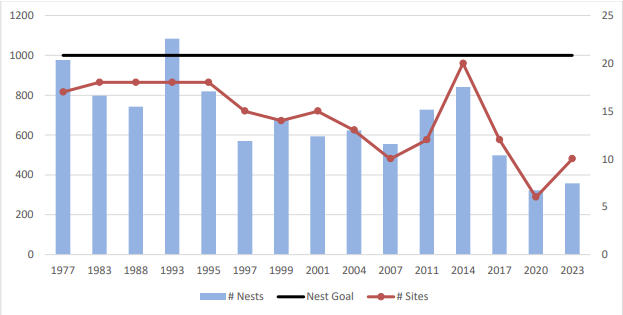

There were about 300 nesting pairs on the Seashore last year, which was an improvement from 2020 numbers but still far below conservation goals. In total, Black Skimmers nested on 10 sites in North Carolina in 2023 (a 67% increase from 2020), with 358 nests recorded according to the survey results. These numbers fall below habitat and population goals for the species set by the committee, as well as the 15-year average number of nests.

All sites used by Black Skimmers in 2023 were natural islands where predation and disturbance by people can easily spook colonies into abandoning their nests. Because they are late nesters, Black Skimmers will often relocate and try again, but the start of hurricane season can make things hard.

Efforts we have taken to improve skimmer numbers include enforcement of posted nesting sanctuaries, predator and vegetation management, and banding. Banding helps us know what areas North Carolina skimmers are using year-round, if they are surviving their first few years, if they are recruiting back into the state’s breeding population, and much more. “It’s important to try to understand where we are losing numbers,” Addison explained, “and over time, that’s what banding and resighting can help us learn.”

Managing nesting habitat for Black Skimmers will also benefit Common and Gull-billed Terns—state-listed endangered and threatened species, respectively—because they nest near each other and have the same nesting habitat requirements.

Perhaps one of the most well-known beach-nesting species, Least Terns have increased above state and partner agencies’ population and habitat goals of 2,000 nests and 25 nesting sites as well as above the 15-year average of 2,285 for the species, with 2,979 nests and 67 sites counted in 2023. Most colonies were on beaches, including our sanctuaries on the south end of Wrightsville Beach—monitored by our Wrightsville Beach Bird Stewards—and Lea-Hutaff Island.

Brown Pelicans are also doing extremely well in North Carolina with 5,227 nests reported in 2023, well above the 15-year average of about 4,000 nests as well as the committee’s population and habitat goals. A noteworthy finding was that nearly all nests (91%) occurred on dredged-material islands with dense grassy vegetation and low, widely-spaced shrubs. “These legacy dredge islands haven’t received sand in many years, in some cases, but they are still paying dividends for species that want to nest in vegetation,” Addison said.

One thing is clear, as coastal development continues to affect birds, they are finding solace on the undeveloped marshes and islands of the Cape Fear River and beyond. That’s why our sanctuary program and partnerships with surrounding agencies are critical for the continued survival of coastal birds.

Two birds that underscore the importance of dredged-material islands are the Royal and Sandwich Tern. These crested terns almost exclusively nest on dredged-material islands with 75 percent of colonies nesting on either South Pelican Island (Cape Fear River), Morgan Island (Core Sound), or Big Foot Island (Pamlico Sound).

Audubon conducted the 2023 count on South Pelican Island, which is one of our managed sanctuaries on the river. The number of Royal Tern nests was slightly below the 15-year average for the species with 12,384 counted in 2023 compared to the average of about 12,610. Sandwich Terns, however, have increased above the 15-year average with 2,572 nests in 2023 compared to the average of about 2,453. They are still slightly below population goals for the species.

Because of their reliance on dredged-material islands with open bare sand, it is essential that these areas continue to be managed for Royal and Sandwich Terns. In this way, managing overgrown vegetation on South Pelican Island has been a big focus for us, as the island also contains marsh habitat that is used by pelicans and Laughing Gulls. “The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission’s habitat division has been instrumental in helping us implment the islands’ vegetation management plan,” Addison said.

The largest of the wading birds, Great Egrets primarily nested on islands, with 50% nesting on dredged-material islands. Nests ranged from islands in Currituck Sound, south to islands in the Cape Fear River, where they nested in trees and dense grass. When taking into account inland nesting pairs, as well as those in the coastal region, Great Egrets are nesting in diverse habitats in North Carolina and are abundant. However, their smaller cousins, Snowy Egrets and Little Blue Herons, are in decline.

Putting it in context

Overall, the 2023 census highlighted the essential nature of much of our management work along the coast. This includes enforcing posted nesting sanctuaries and managing for predators and human disturbance, ensuring coastal projects work for birds and people, and coordinating efforts across agencies. Our coastal team works tirelessly to ensure that birds continue to have a home in North Carolina.

The biggest way to help us protect birds is by respecting posted nesting sanctuaries, keeping your dogs at home or leashed and well away from roped off areas, and telling your friends to do the same. If you’re looking for more ways to protect our coasts, join our advocacy network.