This fall saw the start of Audubon North Carolina’s latest coastal project, an effort to restore oyster reefs on the Lower Cape Fear River.

Oysters are an essential part of the Lower Cape Fear River, where they provide valuable ecosystem services. Because they are filter-feeders that consume small organic particles out of the water column, they also filter the water—up to 50 gallons per day per oyster—removing excess nutrients and sediment. Oysters also provide habitat for a plethora of other species, from tiny invertebrates to commercially important fish species.

They are also, of course, a dietary staple for the American Oystercatcher, meaning restoring oyster reefs on the river will improve the ecosystem for all wildlife, including birds!

Funded through the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation by the North Carolina and Virginia Rivers and Waters Program, our oyster project addresses the first phase of oyster reef restoration: site assessment,project design, and permitting. While some partners on the project are mapping current and historic oyster reef locations and the underwater topography around potential restoration sites, UNC-Wilmington’s Center for Marine Science is helping us monitor the oysters themselves.

Although oysters live most of their lives as sessile organisms, (meaning attached to some kind of hard substrate), they start life as free-floating larvae. On the Cape Fear River, it appears that oyster abundance may be limited by availability of substrate. In order to restore or enhance oyster reefs, therefore, we need to provide suitable substrate in locations where passing larvae can settle down and grow into adults.

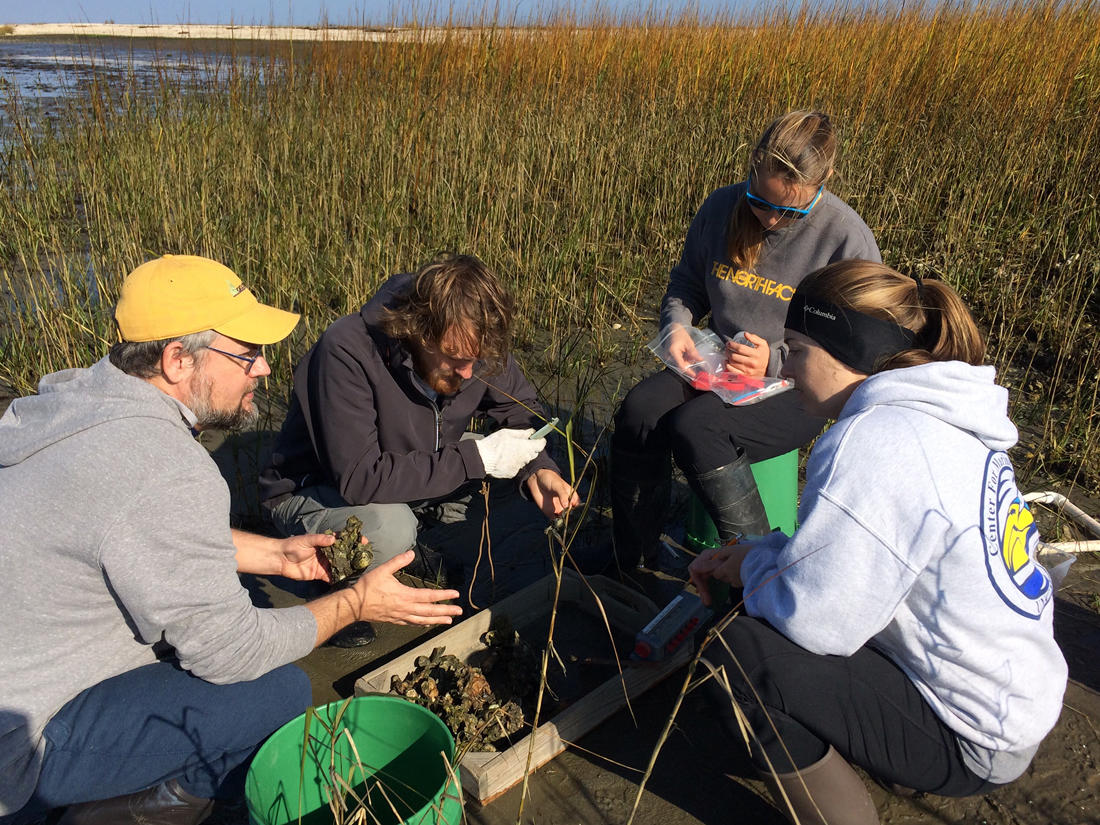

Master’s degree student, Alexis Marti, is studying under Dr. Troy Alphin. Their monitoring work will assess oyster recruitment (how many larval oysters are available in the water column and settle down), abundance, and demography as well as habitat value at each site. Her first field day began with measuring abundance and size demography in several small habitat samples called quadrats: A PVC-square was placed randomly in a potential restoration site, and Alexis measured the number of current oysters in it, and their size. Later, when the water warms enough for oysters to spawn, a ceramic tile will be placed below the waterline and checked for settlement by oyster larvae, which are called spat once they attach to a surface and begin to grow a shell. A sampling tray will also be left at the site, and all organisms that settle in it will be identified and counted, which will measure the biodiversity of each habitat.

Once each potential restoration site is assessed, Alexis and Dr. Alphin will be able to advise us on where to place suitable oyster substrate. They will be looking for locations where there is enough larvae available and enough protection from strong waves and currents that our new reef won’t be torn apart on a windy day.

Once healthy oyster reefs are restored near oystercatcher nesting locations along the Cape Fear River, not only will water quality and marine organisms benefit, nesting oystercatchers will have a nearby food source, allowing them to attend their chicks more closely and provide more protection from predators!

Stay tuned for more updates as this project moves forward.