Now that it’s September, waterbird nesting season has almost entirely concluded in North Carolina, with the exception of a few late pelican chicks that are still waiting to fledge.

As the NC Wildlife Resources Commission and its partners around the state, including Audubon North Carolina, are compiling data, it’s a good time to look back on how the season went.

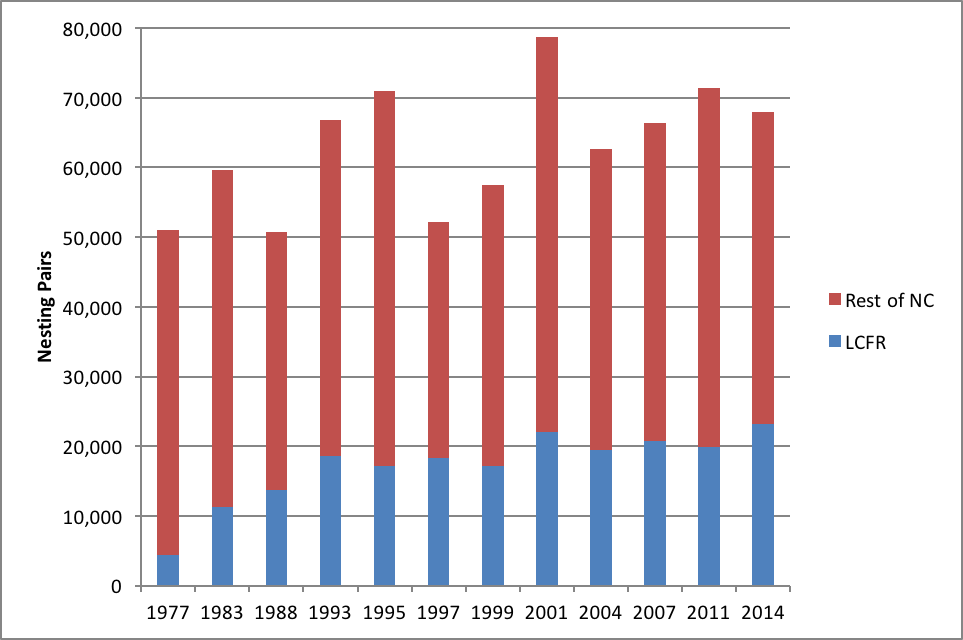

As we discussed this spring, 2017 is a Colonial Waterbird Census year. The tri-annual statewide census counts all nesting colonial waterbird species in order to track population trends and distribution and habitat use. In early May, staff and volunteers began the census by counting wading birds nesting on the Lower Cape Fear River.

The count found 10,167 pairs of White Ibis, 384 pairs of Great Egrets, and 1,293 pairs of Brown Pelicans, among others!

Represented as percentages, this year the Lower Cape Fear River sites hosted about 20% of the state’s Great Egrets and Brown Pelicans, over 25% of its Royal Terns, around 40% of its Tricolored Herons and Sandwich Terns and just over 78% of its White Ibis. Numbers like these make the Lower Cape Fear River one of the largest concentrations of nesting waterbirds in the state.

Although we can’t track productivity (number of young fledged per pair) for all species, most of the nesting birds on the river appeared to do well. Pelican and tern banding by independent research and longtime Audubon North Carolina partner John Weske resulted in 2,515 Royal Terns and 970 Sandwich Terns banded. Since they are banded near fledging, and some fledge before they can be banded, we can assume that at least that number of young terns survived from the Cape Fear River colonies.

We banded 926 Brown Pelican chicks on the river as well. Unlike the terns, where we try to band all offspring, only a fraction of pelican chicks can be banded. However, from visits to the four main colony sites on the river, it appears that all did well, with very little evidence of mortality and large flocks of young pelicans taking flight throughout July, August, and September.

Though we aren’t banding egrets and herons on the Cape Fear River, like the pelicans, their colonies were full of big chicks and new fledglings beginning in late June. Since they start nesting sooner than other species on the river, their chicks also are among the first to fly.

Though the White Ibis nested in excellent numbers on Battery Island and produced many young, there did appear to be some issues with predation by an immature Bald Eagle and Black-crowned Night-Herons in the late spring and early summer. Ibis that nested on the edges of the colony lost young to these voracious predators, both of which are natural predators on wading birds. However, flocks of distinctive hatch-year ibis—they have brown backs and wings and white bellies—attest to the success of other pairs on Battery Island.

At Audubon sites elsewhere in the state, small wading bird colonies of 50 pairs or fewer graced Chainshot Island in Core Sound and Beacon Island at Ocracoke Inlet. And, work to rebuild Wainwright Island in Core Sound resulted in 212 Royal Tern chicks banded and presumed to have fledged out of 537 nesting pairs and 7 Sandwich Tern chicks banded and presumed fledged out of 23 nesting pairs. Predation by Great Black-backed Gulls likely accounted for most of the losses on Wainwright this year.

Meanwhile, data is still being finalized for beach-nesting species, but Lea-Hutaff Island had over 550 pairs of Least Terns, with scores of fledglings seen, and the Wrightsville Beach Black Skimmer colony was again among the largest in the state.

Finally, last but not least, American Oystercatcher productivity increased at two of our sites, with Lea-Hutaff Island fledging at least 10 chicks thanks to overwash from Hurricane Matthew removing some predators from the island and Ferry Slip Island fledging 10 as well thanks to vegetation management.

Though waterbirds always face challenges when nesting we are fortunate to look back on 2017 and find more success than failure around our sites!