For more than 25 years, Audubon North Carolina has managed a network of coastal sites along our state’s coast offering a haven for nesting beach birds. By protecting the specialized habitats that birds need, shorebirds have a chance to thrive. Read on to learn more about sharing our beaches and the big benefits it can bring to our priority birds.

The North Carolina coast is bordered by narrow ribbons of sand called barrier islands. These sinuous, sandy islands stretch from Corolla to Sunset Beach fronting the mainland. Where two barrier islands meet, you’ll find an inlet: a waterway that connects the ocean with the sound. Inlets provide essential habitat for many species of shorebirds like sandpipers, Wilson’s and Piping Plovers, American Oystercatchers and their relatives including:

- Expansive tidal flats rich with food that wintering and migrating shorebirds require;

- Sandy spits that serve as resting and roosting sites that shorebirds need to rest, digest, roost and conserve energy;

- Open or sparsely vegetated sandy habitat that shorebirds need for nesting.

Vital to Species Survival

In 2005, noted shorebird biologist Brian Harrington coined the term “inletophilic” to describe shorebird species that not only need, they require inlets for their survival. He analyzed shorebird distribution and abundance at 361 sites in the southeastern U.S. over many years and found that the lives of seven shorebird species are completely tied to inlets including six listed as “High Conservation Concern” or “Imperiled” in the U.S. Shorebird Conservation Plan.

Preserving Natural Inlets

One of the best inlets in North Carolina for shorebirds is Rich Inlet, located in Pender County between Figure 8 Island to the south and undeveloped Lea-Hutaff Island to the north. Of the twenty inlets in North Carolina, Rich is one of the few natural inlets left in the state. It has escaped hard structures like jetties and terminal groins that drastically alter inlets and destroy habitat that birds require. Rich is also one of the most stable inlets in the state and has remained in the same general location for the past 100 years.

View Rich Inlet from above and you can see the vast sandflats, mudflats and tidepools, as well as sandy spits on both sides of the inlet. These features are typical of large, natural inlets, and they serve as essential foraging, nesting, resting and roosting habitats for many species of shorebirds, including the federally-threatened Piping Plover and Red Knot. The abundance of fish near the inlet as well as excellent nesting habitat attract terns, skimmers and other waterbirds.

Audubon at Work for Shorebird Conservation

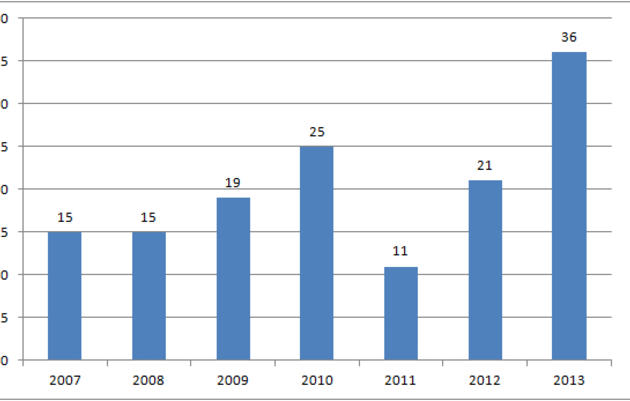

Audubon North Carolina has been monitoring how birds use Rich Inlet since 2007. During weekly surveys, we count all species of birds at the inlet, and over time we have documented its importance to shorebirds and other bird species. We also record locations of Piping Plovers and Red Knots and carefully inspect all shorebirds for bands. Our surveys confirm Rich Inlet is important to shorebirds and waterbirds year-round.

A Thriving Habitat

Last year, more than 800 pairs of Least Terns nested on the large, sandy spit located on the north end of Figure 8 Island, along with American Oystercatchers, Common Terns, Black Skimmers, Piping Plovers, Wilson’s Plovers and Willets. It was the largest colony of Least Terns in North Carolina and one of the largest on the entire Atlantic coast. This year, Rich Inlet is again hosting the largest Least Tern colony in the state. Federally-threatened Red Knots use Rich Inlet during spring migration to refuel during their long journey to breeding grounds in the Arctic. From bands, we know that some have come to Rich Inlet from wintering areas in Brazil and Argentina. Piping Plover from the Atlantic, Great Plains, and the critically-endangered Great Lakes populations also depend on Rich Inlet during migration. Thousands of Canada and Arctic breeding shorebirds like Dunlin, Sanderling, Short-billed Dowitcher, Western and Semipalmated Sandpiper, and Black-bellied Plover are abundant.

It is widely known that many shorebird species are in serious decline. Declines in shorebird populations are driven largely by habitat loss and degradation. Despite ongoing conservation efforts, serious threats to shorebird populations remain and loss of habitat at inlets is high among them; Rich Inlet is no exception. Natural, unaltered inlets are essential to shorebirds and waterbirds. Without these important habitats, shorebirds and waterbirds would not have critical habitat to feed, rest and nest. Audubon and partners are working hard to protect Rich Inlet so thousands of shorebirds and waterbirds have the unique and essential habitats they need to survive. Learn more about Audubon North Carolina’s conservation efforts to protect the seas and shores our birds need to thrive.