Rebekkah Leigh LaBlue is an undergraduate at UNC-Wilmington in the Department of Biology and Marine Biology, conducting honors thesis research on Least Tern egg patterning as it relates to thermal biology. She is a CSURF Paul E. Hosier and SURCA Summer Fellow, with whom she has support for this project. She is supervised by Dr. Raymond Danner.

While the entire Danner lab at UNCW focuses on ornithological thermal biology, my particular interest in the egg arose from the work of alum Robert Snowden, whose thesis centered partly on Least Tern parenting behavior in response to thermal stress.

On my very first day in the lab, Dr. Danner shared with me a collection of 3D-printed tern eggs data loggers: chalky white ovals, delicately hand-painted with speckling of a variety of dark colors and patterns.

I quickly became fascinated with the sheer amount of variation in appearance—and not just between Least Tern nests, but within a single nest.

I chose to study how differential egg patterning contributes to individual heat gain and hatching success, as well as the color-mediated tradeoff between heat gain and camouflage.

Least Terns already breed in temperature-sensitive areas, and so their eggs risk getting too hot to survive with ambient temperature increases of only a few degrees.

For this project I asked, "Does the color of the eggshell influence heat gain?" and, "Does egg color influence nest success?"

I’ve hypothesized that eggshell pigmentation will influence heat gain, with darker and more densely speckled eggs gaining a greater amount of heat more quickly than their lighter counterparts. I also speculated that darker eggs could experience less hatching success.

I will work to establish a kind of heat gain index that is sensitive to the relative dark and light pigment coverage across an individual egg’s surface.

I hope this insight, combined with knowledge of the thermal landscape and substrate composition of a nesting area, can assist in future conservation for these species of concern.

During the months of May and June, I—along with M.S. candidate Lauren Schaale, and the assistance of Audubon North Carolina which manages the island—traveled to Lea-Hutaff Island to collect data on the Least Tern colony.

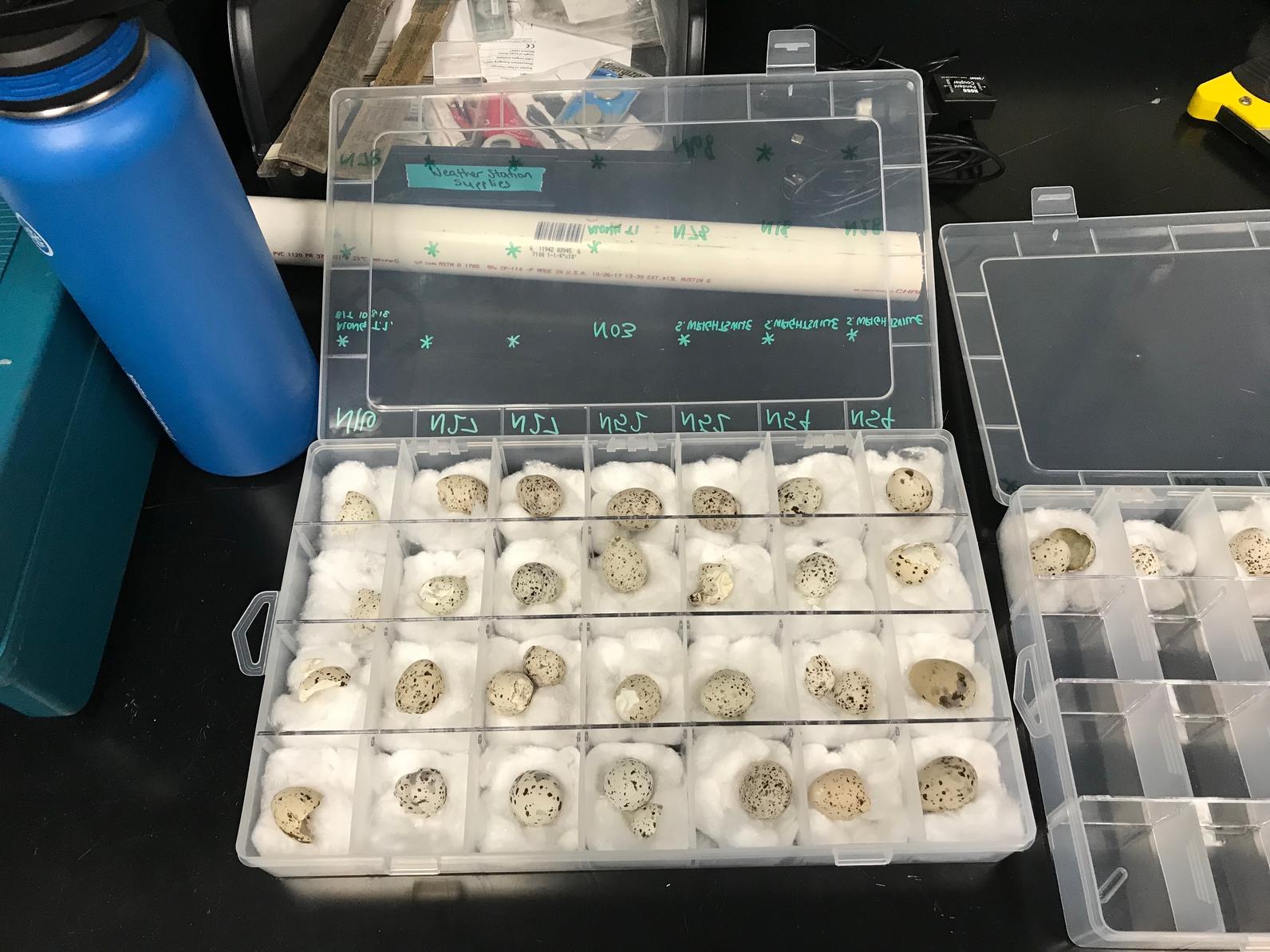

I took standardized photos of the many nests along the beach, tracked hatching success, and collected dozens of failed Least Tern eggs and shell fragments. This fall I will conduct detailed color analysis on these eggs in the lab.

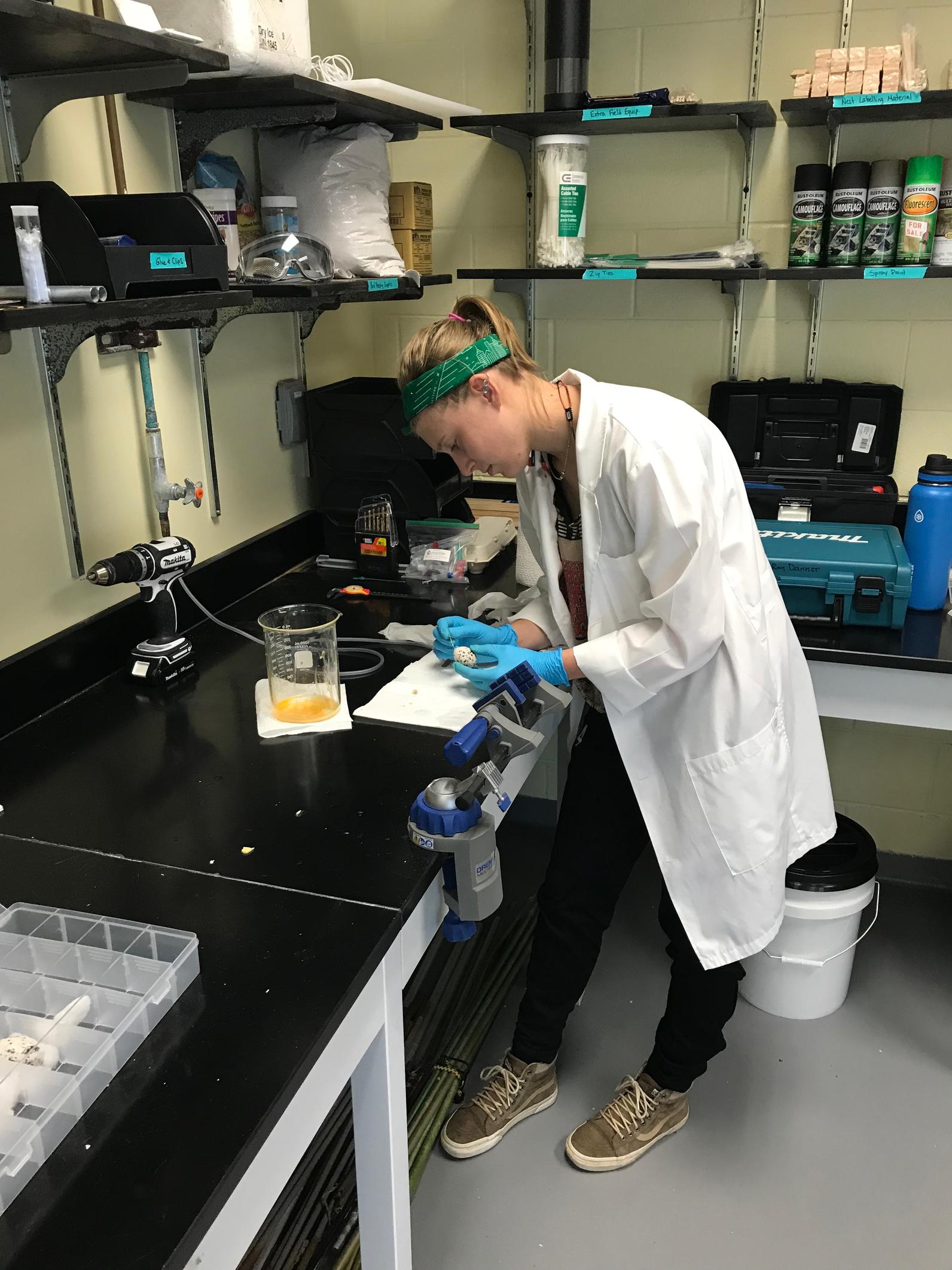

After deyolking non-viable eggs—a task both as fun and as yucky as it sounds!—I also measured egg heat gain on the beach of Lea-Hutaff.

For this task I used a thermal imaging camera to capture detailed photos of temperature across the surface of an egg both in direct sunlight and shaded.

In preliminary analysis I’ve already observed notable temperature differences between and on the surface of individual eggs differing in primary color (density of dark speckling, tint of background) distribution!

Further analysis on the differential rate of heat loss between eggs also promises interesting results.

We’ll check back in later with both of Dr. Danner’s students, Rebekkah and Lauren, to learn more about the results of the research they conducted on Lea-Hutaff Island this summer!