While temperatures dropped well below freezing throughout the state, shorebird biologists working with American Oystercatchers and Wilson’s Plovers were crunching numbers that reminded them of warmer times. Last spring and summer, Audubon North Carolina worked with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission (NCWRC), and its many other partners across the coast, to conduct the statewide American Oystercatcher and Wilson’s Plover census in May and June. Now that the field season is over, NCWRC staff has had time to summarize American Oystercatcher numbers from the census.

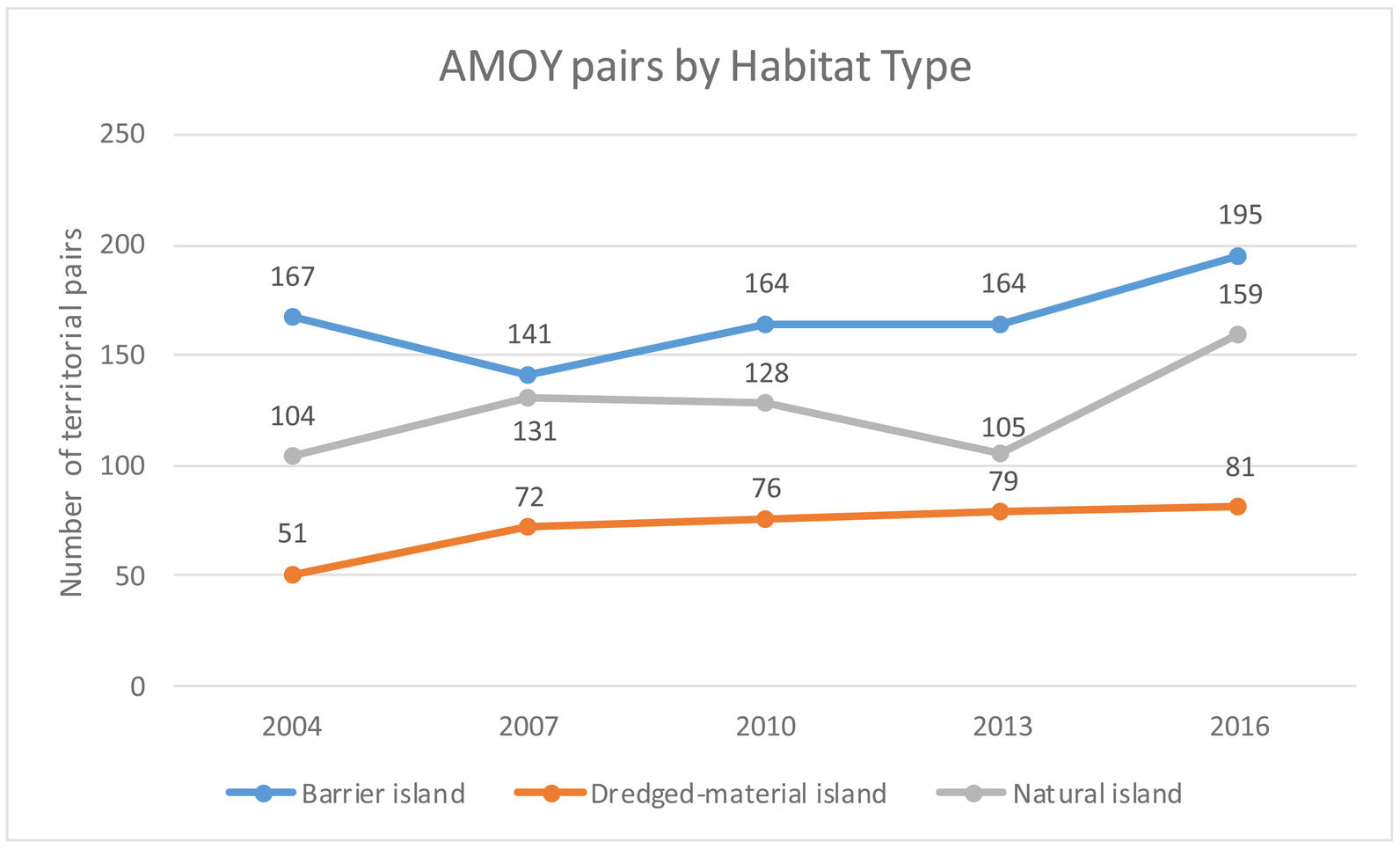

The American Oystercatcher and Wilson’s Plover census has been conducted every three years since 2004 and the data are used to monitor trends in breeding populations of both species. American Oystercatchers are found in a variety of habitats, including in marshes, on dredged-material islands, barrier islands and mainland beaches. Wilson’s Plovers are more particular, nesting only on barrier and mainland beaches, but since their habitat preferences overlap with the oystercatchers’, both species can be counted in a single survey effort.

This is important because, with limited staff and resources, it’s a challenge to cover the entire coast of North Carolina. But this past year, dedicated trained staff surveyed 136 nesting sites along the entire coast visiting the majority of habitat likely to support nesting oystercatchers.

The 2016 American Oystercatcher census was informed by a 2014 study that was carried out in North Carolina by NC State scientists and NCWRC and Audubon staff. That study showed when during the nesting season and the tidal cycle oystercatchers are more detectable. Therefore, the survey timeframe was narrowed to six weeks in May and June and to within two hours of high tide to coincide with peak detectability. This is because, in May and early June, oystercatchers are most likely to be incubating eggs or rearing chicks on well-established territories. It’s also because at high tide their foraging areas are submerged so they are more likely to be on their territories. Pairs are generally easiest to find when they are on territory because they will defend the area with vocal piping displays and flights. So the trick is to catch them when they’re at home.

The 2016 census found a total of 435 pairs of Oystercatchers, an increase from 348 in 2013. This is likely to be good news for oystercatchers, but these are raw numbers that do not account for differences in survey efforts between years or oystercatcher detectability between habitats. Therefore, while we know from intensive monitoring at some locations that pairs have increased—for example, on at Masonboro Island Coastal Reserve—we’ll need to do further analysis to get a better idea of how much their populations increased. For now, the results of the census are positive for the American Oystercatcher and show a generally steady increase over the past 12 years. Continued good management at important sites will help this trend continue into the future.

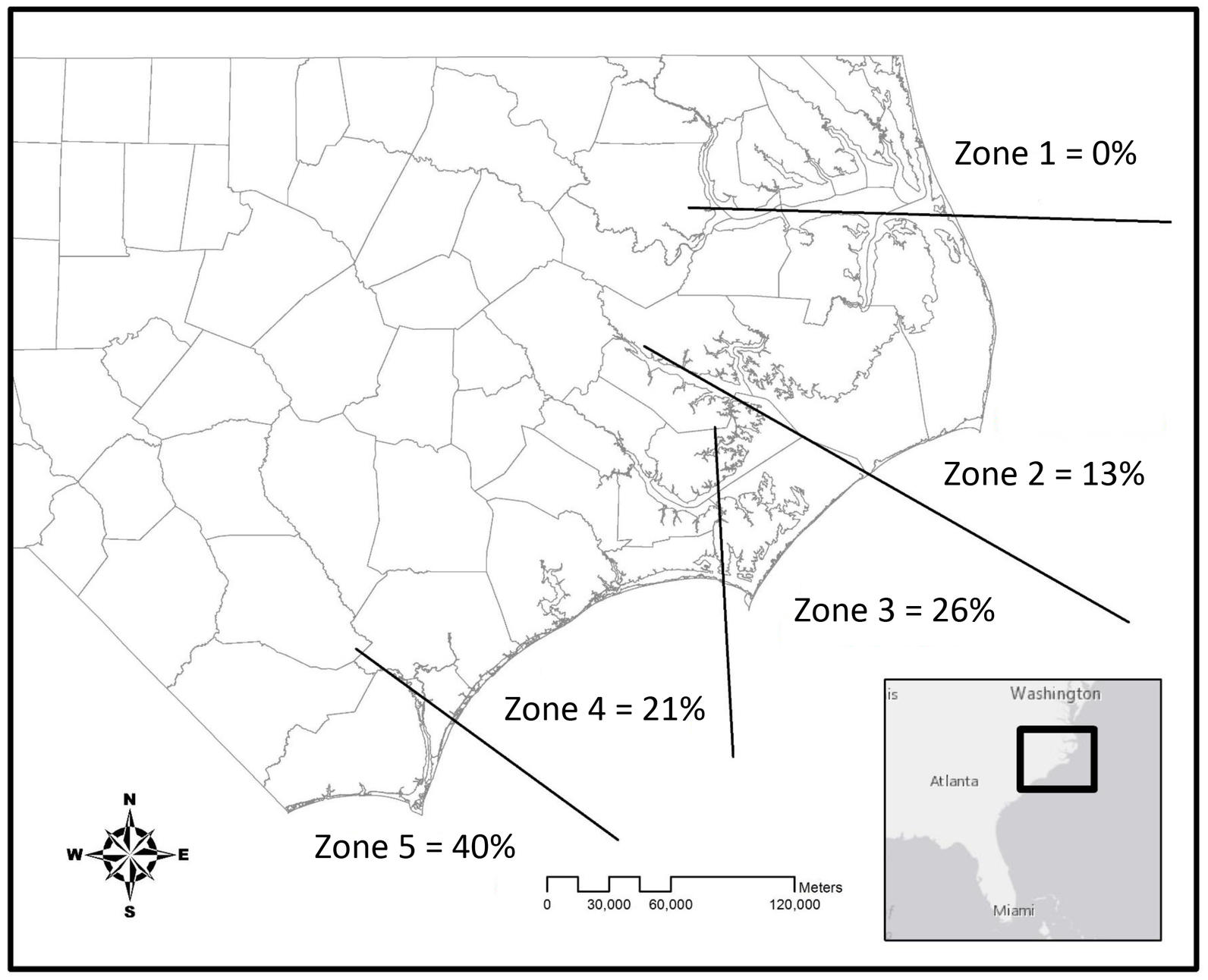

The census also recorded the distribution of oystercatchers in the state by five management zones. The southernmost zone had the largest proportion of oystercatchers. It includes the Lower Cape Fear River where Audubon manages eight islands for nesting birds. The river is home to a large estuarine marsh, where saltwater from the ocean meets freshwater flowing south down the Cape Fear River. Bivalves like eastern oysters and ribbed mussels are plentiful, providing a good food source for oystercatchers lucky enough to stake out a territory adjacent to the shellfish beds. Natural barrier islands are also favorite oystercatcher nesting sites. Lea-Hutaff Island, another Audubon-managed site, and Masonboro Island are also in zone 5, while zones 2 and 3 contain the state’s national seashores and Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge.

Though it’s not as much fun as counting birds outdoors, adding up numbers and summarizing data collected during long days in the field is exciting in its own way. When collected and analyzed, this data tells us the bigger picture about what we were seeing in the field when we were so focused on counting individual nests and pairs and helps guide conservation efforts for American Oystercatchers and other shorebirds.