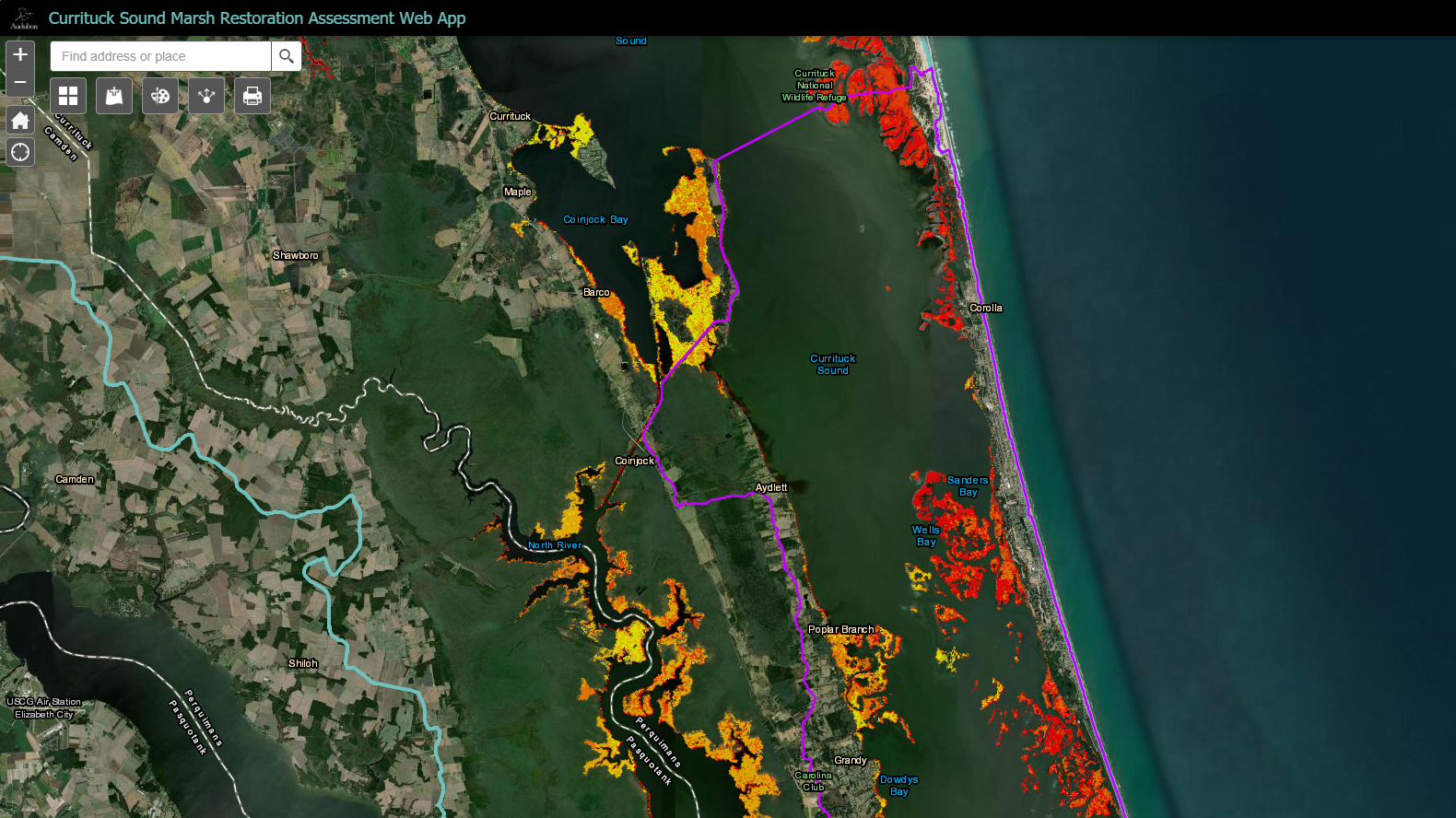

A new web tool from Audubon will help land managers and conservationists better understand where marshes are most threatened on Currituck Sound.

The tool maps habitat across the sound and nearby ecosystems in Virginia’s Back Bay, which flows into the Currituck region, showing the areas of marsh that are most vulnerable to erosion and sea level rise.

The tool will be critical in helping Audubon plan where to undertake marsh resilience projects at the Donal C. O'Brien Jr. Sanctuary at Pine Island, a 2,600-acre sanctuary on Currituck Sound. Because the web app is freely available and easily accessible, other organizations and agencies will be able to use it to prioritize habitat most in need of restoration and protection.

“Marshes are in trouble across Currituck Sound. The web app allows all conservation groups working on the sound to make smart, science-based decisions about where to protect and restore our most vulnerable wetlands,” said Cat Bowler, coastal resilience program manager at Audubon North Carolina.

The web app uses information from a federal data set called the National Wetlands Inventory, which breaks down Currituck marshes by type—from estuarine and marine wetlands to a variety of freshwater marsh habitats, all of them present in Currituck Sound.

It also helps conservationists plan for the future. As sea level rises, marshes have the ability to gradually shift inland with the advancing water as long as space is set aside to allow for this shift—a process known as "marsh migration." The web app uses data from several sources, including The Nature Conservancy’s Resilience Coastal Sites for Conservation in the South Atlantic, to help identify areas that are best suited for marsh migration, mapping out the places that need protection today to allow for marsh growth in the future.

The extensive wetlands of Audubon’s Pine Island Sanctuary and throughout Currituck Sound are among the most important places in the hemisphere for birds, providing critical wintering grounds for waterfowl and nesting habitat for egrets, herons, rails, and many other water birds. The tool will help better protect this habitat for birds, but people will benefit as well.

The tool includes additional layers that allow users to view socioeconomic factors of local communities—indicators such as household income and poverty rates—as well as nearby critical infrastructure, like hospitals, roads, and schools. This enables decision-makers to consider how the location of natural infrastructure projects—like living shorelines and open space preservation—would benefit surrounding communities.

Resilience projects help revive and protect wetlands that in turn ensure Currituck Sound remains a destination for outdoor recreation, hunting, and wildlife watching, all activities that support local economic development. It also provides communities with protection from storms and rising seas.

The web tool helps organizations and agencies visualize all of these factors and incorporate them into conservation planning. “By taking this holistic approach, we make sure our conservation work is creating a better future for birds and communities on Currituck Sound,” Bowler said.

Officially called the Currituck Sound Marsh Restoration Assessment Web App, the tool was created with input from the Currituck Sound Coalition, an Audubon-led partnership of local non-profits, academic institutions, community organizations, and government agencies.

The group worked with the science division of the National Audubon Society to provide feedback and the best available data for the app. Joanna Grand, PhD, senior spatial ecologist with the National Audubon Society, has high expectations for how land managers throughout Currituck Sound can use the tool.

"It will be a useful decision-support tool that managers of the severely threatened Currituck Sound marsh system can use to help inform their restoration strategies,” Grand said. “We've been co-developing the tool with many of them and expect they will be eager to explore it.”

Audubon recently used the tool to select two high-priority areas—one at Pine Island Sanctuary, and another at the Currituck Banks National Estuarine Research Reserve—where we will work with partners on two marsh resilience projects.

The project is part of a larger restoration planning initiative funded by three grants totaling $300,000 from the North Carolina Clean Water Management Trust Fund, North Carolina Environmental Enhancement Grant Program, and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation's National Coastal Resilience Fund.